This month I’ve been reading about Indigenous language, why it’s so important, and how it can be revitalized. More specifically I’ve been reading about Indigenous language revitalization and reclamation (ILRR) which is a term used by Dr. Paul John Meighan in his manuscript-based PhD thesis What is language for us?. Dr. Meighan defines language reclamation as “reclaiming of cultures and knowledge systems decimated or still threatened by colonization or colonialingualism”.1 Dr. Meighan’s main argument is that Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK), combined with technology (TEK-nology), can enhance immersive, Indigenous-led language revitalization and reclamation in the Canadian context. As a non-Indigenous Scottish Gaelic researcher, Meighan also brings a relational, kincentric, community-led methodology called Dùthchas as a way to foster respectful working relationships with his Anishinaabe family (through marriage) and their community in Ketegaunseebee.

For his TEK-nology pilot project Dr. Meighan created a series of YouTube videos designed to be short, fun and relational to engage learners of all ages in conversation-based, experiential learning. The videos use graphics and emojis to teach new words and phrases, as concepts and community-based teaching are valued over “decontextualized, disembodied grammar”.2 Reading firsthand accounts of people learning Anishinaabemowin, I was struck by the insignificance of grammar and spelling, especially during language learning.

Learning about people’s experience with the language and its inter-relatedness with the community and the land made me rethink language and my colonial understanding of it. In light of my research interest, I need to remember that while syllabic characters and orthography play a role in written language as isolated elements, they are not language. Unlike colonial languages like English and French, Indigenous languages such as Anishinaabemowin have a relational, place-based connection.3

Culture, language, teaching, and place are all connected in the worldview of Indigenous Peoples. Because of this, there are overall health and wellness impacts that language fluency — or even conversational language ability — can have on the community. “An important study with Indigenous communities in British Colombia reported that ‘youth suicide rates effectively dropped to zero in those few communities in which at least half the band members reported a conversational knowledge of their own “Native” language’”.4 In Decolonizing Data, Jacqueline M. Quinless provides empirical evidence that participation in Indigenous language use “offsets some of the adverse impacts of colonialism”.5 This positive correlation seems obvious, given that embedded teachings and knowledge are part of Indigenous languages.

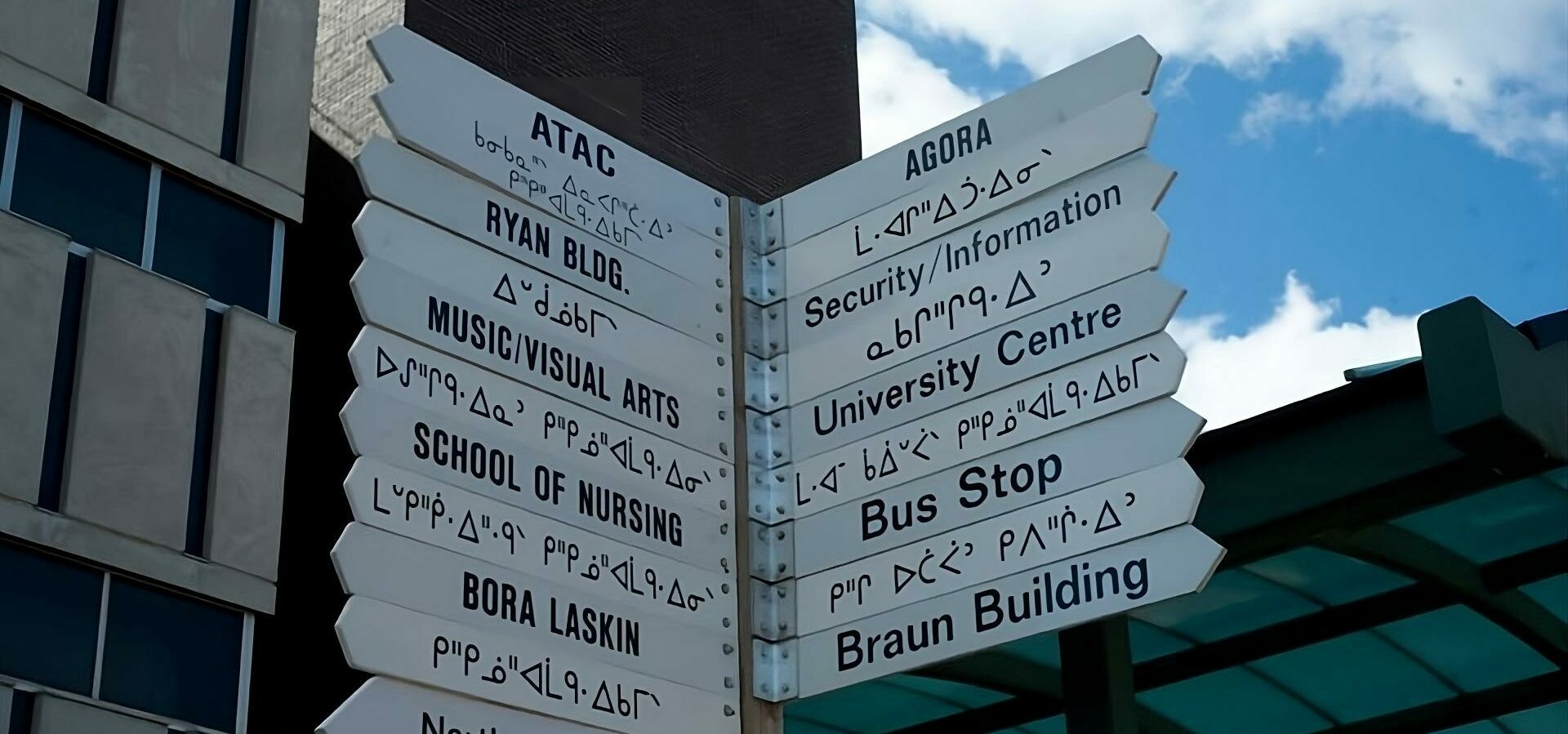

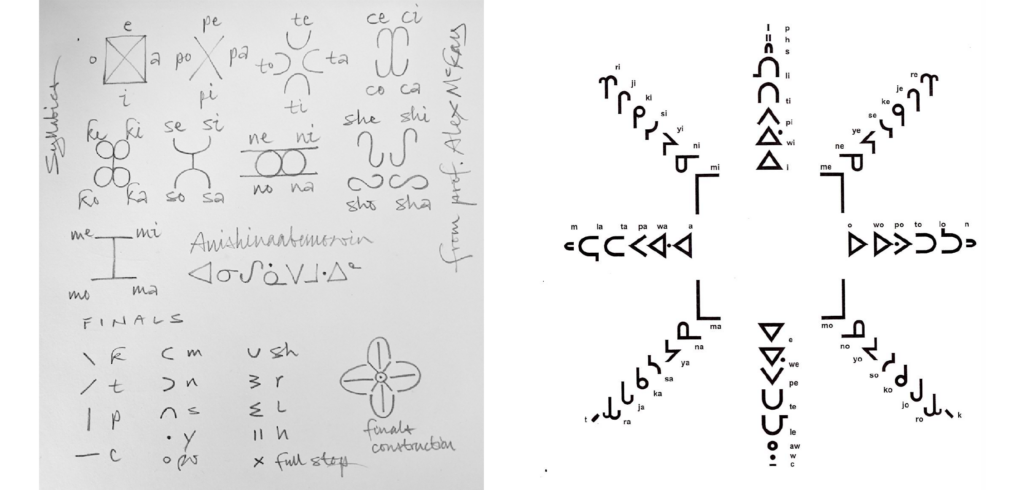

Left: Study by Kevin King.6 Right: Syllabic Star Chart.7

Written Language

The Anishinaabe language and way of life continue to be taught orally and through action rather than the written word. Consequently, written language has a supporting role in Anishinaabe communities with strong oral, community-based language use. However, in Northern communities such as Nattilik, where language fluency is low, pronunciation of Nattilingmiutut can no longer be approximated and correct phonetics plays a more prominent role.8

Indigenous North American Type, the corresponding essays, and Google Fonts knowledge pages first drew me to this area of study. I first read Kevin King’s essays in four months ago when I only had a vague idea of what my research topic was going to be. Returning to the essays now, I have a greater understanding of how syllabics function and the challenges involved in using them. A diagram by Kevin King (shown above) demonstrates nine of the consonant-vowel pairings and their relationships to rotations, which helped me finally understand the spatial understanding of syllabics and their inherent simplicity. From this jumping-off point, I learned about the syllabic star charts used in Cree. I learned that the Cree language, called nêhiyawêwin, is sacred, and the syllabics are called Spirit Markers. Videos of Indigenous teachers showing how to sound out the syllables and their relationship to the star chart further made me appreciate the simple sophistication of how syllabics work. In nêhiyawêwin traditional teaching, the syllabic star chart connects to the grandfather and grandmother directions, which correspond to the cardinal and ordinal directions, respectively.9 It’s challenging to explain, but the videos above demonstrate clearly how the shapes and sounds work together with the different directions.

As promised, I will share the type design books I have been referencing in my next post and, in a future post, instructions on installing syllabic software keyboards for macOS, Windows, and iOS.

- Paul John Meighan, “What is language for us? The role of relational technology, strength-based language education, and community-led language planning and policy research to support Indigenous language revitalization and cultural reclamation processes” (McGill University, 2023), https://escholarship.mcgill.ca/concern/theses/bz60d3092, 28. ↩︎

- Meighan, “What is language for us?”, 23. ↩︎

- Meighan, “What is language for us?”, 25. ↩︎

- Darcy Hallett, Michael J. Chandler, and Christopher E. Lalonde, “Aboriginal Language Knowledge and Youth Suicide,” Cognitive Development 22, no. 3 (July 2007): 392–99, quoted in Meighan, “What is language for us?”, 193. ↩︎

- Jacqueline M. Quinless, Decolonizing Data: Unsettling Conversations about Social Research Methods (Toronto Buffalo (N.Y.) London: University of Toronto press, 2022), 98. ↩︎

- Kevin King, “Typotheque: Syllabics Typographic Guidelines and Local Typographic Preferences Article on Typotheque by Kevin King,” January 24, 2022, https://www.typotheque.com/articles/syllabics-typographic-guidelines. ↩︎

- Endangered Alphabets Project, “Atlas of Endangered Alphabets: Indigenous and Minority Writing Systems, and the People Who Are Trying to Save Them.,” December 18, 2018, https://www.endangeredalphabets.net/alphabets/canadian-aboriginal-syllabics/. ↩︎

- Kevin King, Indigenous North American Type. (Typotheque, 2023), 5. ↩︎

- Amiskwaciy History Series, “History of the Cree Language Part 1,” YouTube, 2016, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CpvuED_hJTM&t=1180s. ↩︎

Featured image: English and Oji-Cree wayfinding at Lakehead University. Source: Lakehead University on Facebook